May is Domestic and Family Violence Prevention (DFVP) Month. It is held each year to raise community awareness and promote a clear message that domestic and family violence will not be tolerated in our communities. The impact of domestic and family violence is overwhelming. It is also the leading cause of youth homelessness.

A woman has been murdered by a partner or former partner every 3 days during DFVP Month so far. By May 18th 6 women have died at the hands of their current or former partner.

Over the years the Queensland government and partners have worked tirelessly to say Not Now Not Ever together to end the scourge of domestic and family violence. The commitment is solid, the resources are forthcoming, laws have been changed and partnerships including a taskforce are in place. Across the country many similar endeavours are evident. Yet during May more women died at the hands of those who were meant to love and care for them.

It is clear that there is no holy grail in ending domestic and family violence. Halting the behaviour of those who exert power over others is proving to be a mission. Hopefully it’s not a mission impossible. After years of campaigning we’re beginning to recognise that relationships are mutual but violence certainly isn’t. For decades both were intertwined in the systems responses to those experiencing violence at the hands of a partner or former partner.

Whilst we focus attention on women and children in the prevention of domestic and family violence in our society because they are so regularly the targets of violence, it appears that in truth that domestic and family violence has nothing to do with women and children other than the obvious gendered violence link. We live in a society where bullying and abuse of power is everywhere – in workplaces, schools, institutions, systems, families and homes. What if the way we look at violence is flawed and the way we treat victims and survivors is equally so? What if women who experience violence are strong, solid and resistant to violence and the perpetrators are only powerful because our systems permit their power?

Canadian Psychologist and violence expert Dr Allan Wade is clear that the majority of victims of violence use resistance to thwart violence. Yet our society sees them as both passive and/or mutual in the violence. Furthermore, he argues that there are social responses that dissuade those who experience violence from speaking out and recovering: “How victims respond to perpetrators is tied to the social responses we all create.“ He outlines that our use of language is central to our tendency to hold victims accountable for their abuse whilst letting perpetrators off the hook. He further argues that the only way of combating abuse and violence is to insist perpetrators be 100% responsible for their behaviours and this will occur when they know there will be serious consequences for the abuse they perpetrate.

Dr Wade, much like many of the professionals from the domestic violence sector says it’s long overdue for us to end the focus on women who are abused and instead pay attention to perpetrators of abuse. They need to be the focus and their rehabilitation needs to be the intent. We need to shift the responsibility from victim to perpetrator. Research clearly demonstrates that a woman is most at risk of serious harm and/or death when she makes the definitive decision to leave an abusive relationship. Multiple systems responses and significant supports need to be in place to assist such a radical and dangerous decision in these circumstances. We wouldn’t let our Police or armed forces go into a situation of serious threat without back up. Why would we expect a woman to do so when dealing with a violent and abusive partner?

One argument is that we expect women to stand up to their perpetrators because theirs is or was a mutual relationship they chose to be in. So we also mutualise the abuse. We ignore the reality that perpetrators con victims. Then they blame victims and co-opt others to join their tirade. The abuse creeps in over time. On some level surely she agreed to all of this reality in its totality? She is still there, isn’t she? Again experts like Allan Wade argue there is nothing mutual about abuse and there is no such thing as an abusive relationship. Whilst relationships by their very definition are mutual, abuse is not. It is a power dynamic of one partner flexing their muscles against another. He notes domestic violence offending as a choice by one person to exert power and control over another. Whilst gendered violence is a huge issue in our society and communities, social response is another key factor that Dr Wade sees as integral to the domestic and family violence intervention conversation. “The research about social responses is very clear. When people get a negative social response they are highly unlikely to ever disclose again. It’s not just violence they’re fearing, often they’re fearing negative social responses that are just as painful or as harmful.”

We all know that we need connection for our holistic wellbeing. That is clear in research and evidentiary practice related to children, young people, families and communities. We thrive when we connect and feel a part of a community or something bigger than ourselves.

Dr Wade notes this reality and further states that victims of violence who receive positive social responses and are cared for by their peers, family, professionals and others are much more likely to recover. “They’re also more likely to feel more stable and able to cooperate with authorities and follow through with court processes and pathways to wellbeing” he said.

“If you want to understand how victims respond and resist and how offenders use violence you must take into account social responses.”

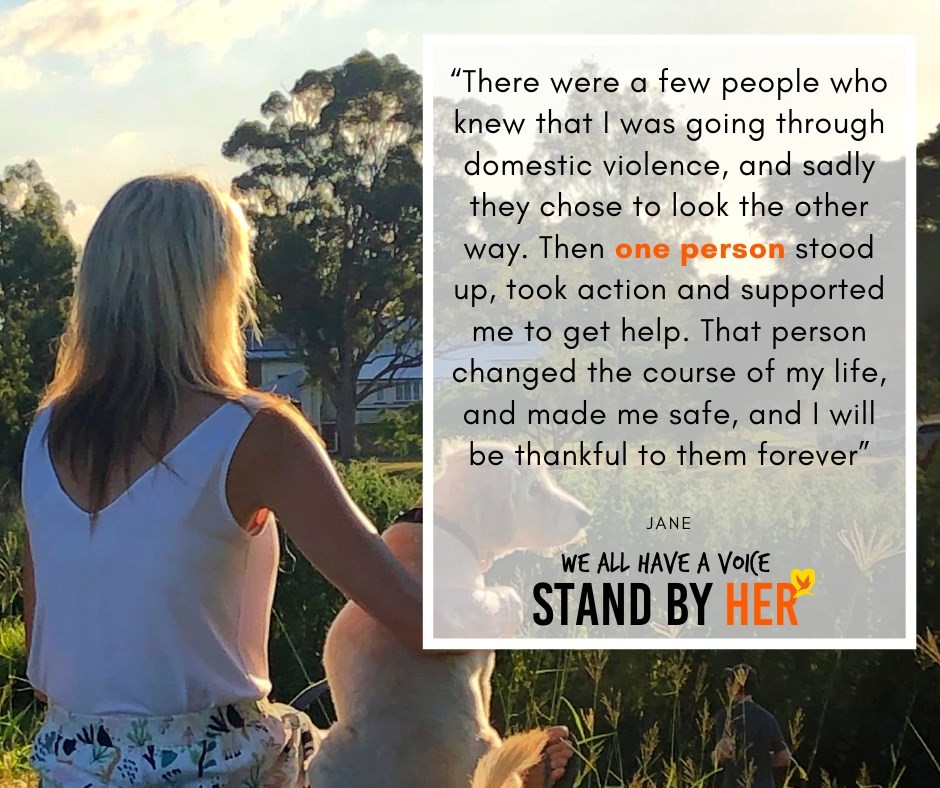

In Queensland when we talk about bystanders and speaking out as per the Brisbane Domestic Violence Campaign and image presented above, that goes some way to addressing what Dr Allan Wade is talking about. We have a long history of victim blaming and language that holds victims to account for the behaviours of perpetrators they played no part in and had no say in. We’re finally changing how we perceive and articulate domestic and family violence. We’re making inroads but we still have a long journey ahead of us before women and children in our society are safe and can experience holistic wellbeing. In part that’s due to our society as a whole experiencing factors of abuse of power that are commonly understood, excused and accepted. It’s also about how we view women and children and accept their maltreatment.

In any status quo where power over is accepted there will always be those seen as lesser than and this is a factor we need to address. More importantly, the responses to harm and violence by those in the community can go some way to mitigate the harm being perpetrated. Ultimately we are social beings and need connection to thrive and experience wellbeing. Social responses are essential. When treated positively, we can cope with difficult circumstances. When treated poorly, any trauma is magnified.

You can be an active bystander by calling the Police if you hear your neighbour in distress or by calling BDVS for advice if someone you know is experiencing DV.

Phone (07) 3217 2544

Email (non-urgent) bdvs@micahprojects.org.au

www.bdvs.org.au

If you need emergency help you can also contact:

- Police on 000

- DVConnect Womensline on 1800 811 811 (24 hours, 7 days a week)

Note: This number is not recorded on your phone bill

- DV Connect Mensline on 1800 600 636

- National DV line on 1800 737 732.